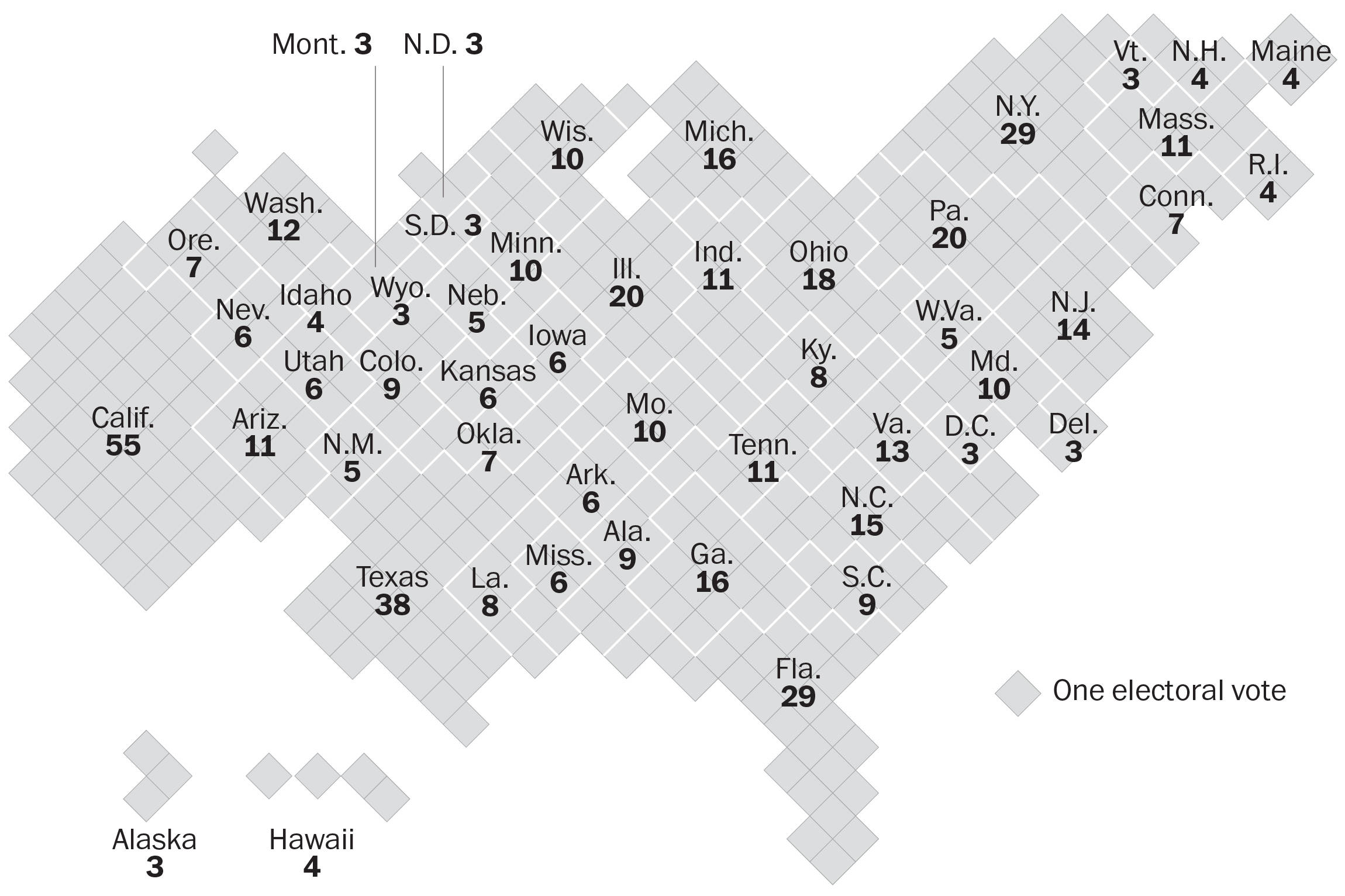

| By the end of the day, President-elect Joe Biden's win will be more than just a projection. The electoral college is voting Monday, and they're going to confirm that he won the election. The nation's founders set up the electoral college in part to give less-populated states more sway in choosing the president. It serves that function to this day. Biden won millions more votes than President Trump, but the number that really matters is the 306 electoral votes he pieced together from different states, well over the 270 needed to win. Biden could receive 270 votes by the time you read this newsletter.  (The Washington Post) | Here's the two-second version on how the voting works, with a more in-depth explainer here: - Electors are meeting in their respective states throughout the day and casting their votes to certify which candidate won their state.

- They need to do this in person to sign official documents, but most states are taking safety precautions to prevent electors from catching and spreading coronavirus.

- The certificates will go to Congress to count in January and make Biden's win officially official. Some Republican lawmakers are planning to challenge the results, but their challenge will fail. After that, there is nothing left to do but inaugurate Biden.

A few other things to know about the electoral college  Members of the electoral college are sworn in in Boston on Monday. (Charles Krupa/AP) | Electors may sound mysterious, but they're mostly party loyalists chosen by party leaders for this job. This year there are governors acting as electors. Hillary and Bill Clinton are electors in New York. But so is a college student in Texas and a retired social worker in Wisconsin, report the Wall Street Journal. In most states, electors are legally required to cast their votes for the candidate who won that state's popular vote. The Supreme Court ruled this year that states can punish "faithless electors" who swap their vote at the last minute, but few states have significant punishments in place. Don't expect any shenanigans, though. Electors are loyal to the party that won that state, so it's highly unlikely that 10 Democratic electors from Wisconsin, for example, are going to suddenly vote for Trump. (None of them did.) That's why Trump spent the past month trying to convince Republican state legislatures in states he lost to (most likely illegally) assign electors to him. No one took him up on that. So far Monday, votes are proceeding smoothly. We have a running tally of the vote and livestreams of states still voting. There is a growing movement to circumvent the electoral college, where states give their electoral votes to the candidate who won the national popular vote rather than their state's popular vote. State legislatures totaling 196 electoral votes have passed a bill to do this. But for this to go into effect, they need states totaling 270 electors to join. And that's a challenge. Republican states benefit politically from the electoral college and see no reason to change it. The politics of a vaccine  Physician Avish Nagpal, who treats patients in Fargo, N.D., receives the first shot of the coronavirus vaccine given in North Dakota on Monday. (Dave Kolpack/AP) | Monday is a really big day in America. As we finalize a new president, the first Americans are getting inoculated against the coronavirus. Trump was furious that vaccine-success announcements came shortly after he lost reelection. And to the extent that he's focused on the vaccine now, it's to try to take credit for how quickly it's come together. He's been pitching a narrative that only he foresaw what was possible when others doubted him. Here's the reality, writes The Washington Post's health team: "The lightning-fast development of two leading coronavirus vaccines happened both because of and despite Trump — perhaps the most anti-science president in modern history." In an investigation into how Operation Warp Speed came together, they find that Trump administration officials and scientists realized that if government covered the risky costs of making a vaccine before scientists even had one, things could move a lot quicker. It worked, especially with Trump's backing — who foresaw a political opportunity in getting a vaccine to Americans as quickly as possible. The irony of all this is that Trump is a president, my colleagues write, who "previously flirted with anti-vaccine views and savaged those who cited scientific evidence to press for basic public health measures in response to the pandemic. The lifelong businessman who refused to wear a mask himself was able to understand vaccines as something else entirely: a deliverable that he could make happen with money." Biden's Cabinet diversity problem, but not in the way you think  Biden has nominated retired Army Gen. Lloyd Austin III to lead the Defense Department. (Susan Walsh/AP) | Biden is fulfilling his promise to have one of the most diverse administrations ever, in terms of color and gender. But what about age and resume? Some younger activists worry that Biden is picking too many people he knows from his days in the Senate, or from the Obama administration, rather than people with new ideas that speak to younger progressives, report The Post's Seung Min Kim and Annie Linskey. "There's more appointments of color, but there is a lot of same old, same old," one concerned activist told them. | By Ashley Parker, Amy Gardner and Josh Dawsey ● Read more » | | | |